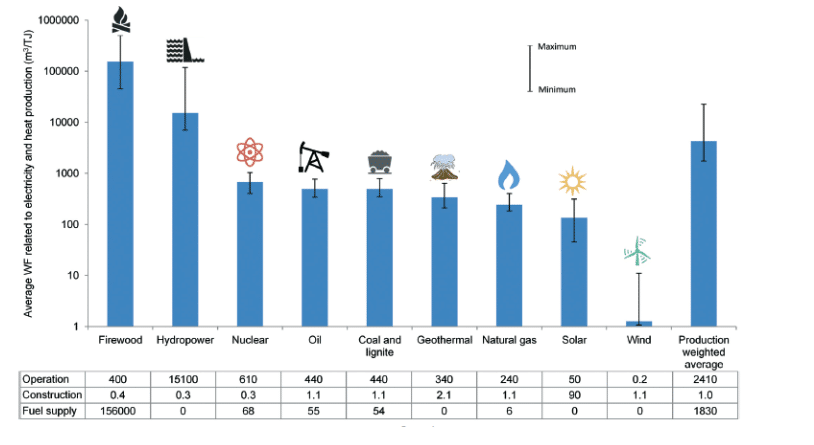

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), 10% of global water withdrawals and 3% of water consumption are linked to electricity and heat. It’s global weighted average Water Footprint (WF) is estimated to be 4,241 m3/ TJe, the equivalent of 2 Olympic swimming pools to cover the energy demand of 69 European homes.

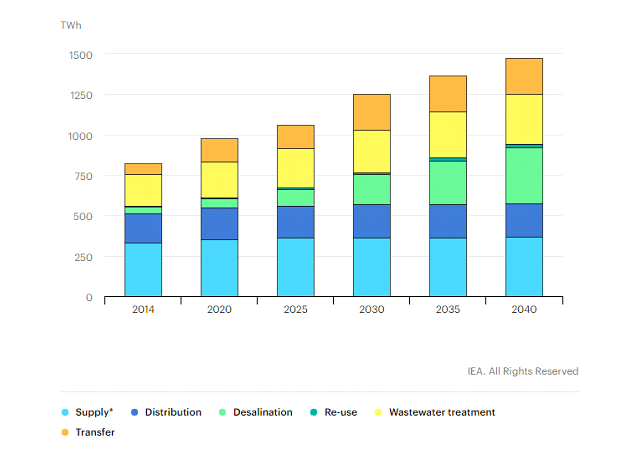

Water and energy are inherently linked to each other. For example, energy is vital for water processes, including distribution, wastewater treatment and desalination. The energy is mostly used as electricity and represents about 4% of the global electricity consumption[2]. Likewise, energy production requires large amounts of water.

Biofuels for example, particularly first generation biofuels, consume large amounts of water for crop growth. Fossil and Nuclear energy are also water intensive. Activities such as coal and uranium mining, drilling and fracturing require an important volume of water.

The reduction in freshwater availability would create stronger dependence and reliance on other energy intensive water sources for supply such as desalination. That trend is shown in Figure 1.

That is why, adopting available energy efficient measures and enhancing the energy recovery potential would be beneficial for all parties. Wastewater is particularly valuable, given that it contains energy that can be harnessed and reinserted into the electric system at the waste water treatment plant. This action can cover up to 50% of the plant’s energy needs.

The fossil fuel industry consumes vast amounts of water, therefore has a large water footprint. This fact is particularly fundamental to consider in the energy transition. New technologies must emphasize on reducing the water footprint throughout the production chain, just as it is being intended with carbon emissions. The question is, are renewables following the right path as an overall sustainability alternative? Figure 2 shows a comparison between the WF of different power alternatives.

Figure 2 shows that renewables do have a lower WF than fossil energy carriers, yet this is not always the case. Firewood and the biomass sector in general have a larger WF than the rest of the energy systems. This is accountable on the intensive agricultural water use for crop irrigation. In the specific case of biomass, the WF is lower if all the available material is used (stems, leaves, branches, etc.) to generate electricity instead of producing biofuels [4].

Likewise, it is interesting to observe the share of energy sources in the world’s total energy supply, which is shown in Figure 3.

![Figure 3: Share of energy sources in the world's total energy supply based on EIA's reference scenario (a) 2012; (b) 2035[3]](https://bosaq.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Figure-3-1.png)

Figure 3a and Figure 3b show the expected variation in energy between current and future times. Considering the 2035 outlook as a realistic scenario, if no adequate water management measures and policies are adopted, water withdrawal for energy purposes is most likely to remain the same. This would endanger the remaining water sources on which future generations will rely on.

Renewables have the opportunity of reducing the water footprint of energy production. For this reason, efforts should be focused towards implementing technologies including hydro, wind and solar energies, which have a lower WF. On top of that, pointing to inclusive solutions that integrate clean energy and water as well as modelling and integrating energy and water efficient utilities. This will result in greater benefits for all.

Additionally, wastewater reuse systems can be used as a balancing asset for demand response. On-site grey water reuse can reduce freshwater withdrawals, resulting in less effluent runoff. Implementing wastewater reuse systems, can improve reliability in supply by up to 17% [5].

Water experts can help you in treating your wastewater and revalorize the water you have at-hand. Our team of experts will find the most optimal solution for your needs and advise you on how to decrease your water footprint in your organization.

[1] M. Mekonnen, H. G., and A. Hoekstra, “The consumptive water footprint of electricity and heat: a global assessment,” Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 255–396, 2015.

[2] “Energy and water – Topics - IEA.” [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/topics/energy-and-water. [Accessed: 21-May-2020].

[3] S. Hadian and K. Madani, “The water demand of energy: Implications for sustainable energy policy development,” Sustain., vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 4674–4687, 2013.

[4] W. Gerbens-Leenes, A. Y. Hoekstra, and T. H. Van Der Meer, “The water footprint of bioenergy,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 106, no. 25, pp. 10219–10223, Jun. 2009.

[5] K. R. Piratla and S. Goverdhanam, “Decentralized Water Systems for Sustainable and Reliable Supply,” in Procedia Engineering, 2015, vol. 118, pp. 720–726.